In a previous SandHill article, my colleague Mark Hauser and I detailed the Subscription Scorecard, a modernized balanced scorecard that is centered around the customer and takes into account the unique nature of the subscription model, where recurring revenue and growth drivers matter the most and non-financial-statement metrics have increasing weight.

In that article, it was established that there are two main drivers of SaaS company valuation multiples: revenue growth and margins. To manage and predict future revenue growth and profitability, a company must thoroughly understand its relationship with its customers. At the heart of that understanding are two key metrics that often are — and should be — evaluated together: customer lifetime value (CLTV) and customer acquisition cost (CAC). Individually, these metrics can provide insight into expected future revenue and expenses. When used in tandem, they can provide even greater insight.

In this article, we delve deeply into these two metrics, highlighting various ways each can be calculated and providing examples of real-world applications.

Customer lifetime value (CLTV)

CLTV is the expected revenue generated from a customer over the course of your relationship with that customer. It can take many factors into consideration: revenue per customer, contract length, renewal rates, gross margins, etc. Your choice of calculation method will depend on your company’s business model, strategy, maturity and other factors.

Here are just a few of the ways CLTV can be calculated, starting with the simplest approach and increasing in complexity as they progress:

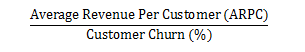

CLTV method 1

This is the simplest calculation method, but it doesn’t take much into consideration. It takes the average revenue per customer (ARPC), which is calculated from either your monthly recurring revenue (MRR) or annual recurring revenue (ARR), then divides it by the time-matched customer churn rate (churn), which provides the proxy for how long you will have a customer.

Usage: This approach can be leveraged when a simple or quick calculation is needed, gross margins are very high (95 percent or more), gross margins are unknown (new product) or there is no expansion revenue expected over the customer lifetime.

Two things to note:

- ARPC and churn need to be calculated with corresponding time frames. For example, if monthly recurring revenue is used for ARPC, then churn should be monthly. If ARR is used, then churn should be annual.

- Churn rates should be for the number of customers lost during a given time period (1 – customer retention), not revenue ($) churn.

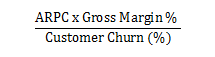

CLTV method 2

This calculation method builds on CLTV method 1 but accounts for the ongoing costs of providing services to your customers. You may want to include a portion of R&D expenses within the top of the equation if you view product enhancements and improvements that come out of R&D as a way to deliver value to current customers and reduce overall churn.

Usage: This is the most common approach taken, and it should be leveraged when gross margins are known and fairly stable.

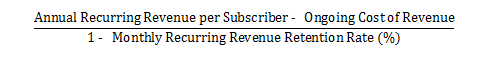

An example of a company using a slight variation (but effectively equivalent) to this method is MINDBODY, Inc., which operates a cloud-based business management software and payments platform for small- and medium-sized businesses in the wellness services industry. It described the following calculation method on an analyst day presentation [endnote 1]:

MINDBODY highlights this metric in order to communicate its compelling unit economics. (We will revisit this example later in this article to better understand how and why this information is shared.)

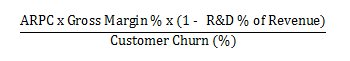

As mentioned above, some may choose to include R&D in this view. With R&D included, the formula becomes:

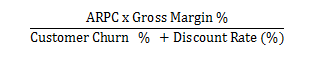

CLTV method 3

This approach is largely similar to CLTV method 2, but it adds in a discount rate to the denominator that accounts for revenue received in future years not being as valuable as revenue received in more current years. The discount rate used will typically be your company’s cost of capital, assuming the rate is known.

Usage: This method is often used in public companies that have established costs of capital. Expenses to acquire customers occur in current years, so revenue generated from those customers in future years should be discounted back to generate an appropriate comparison.

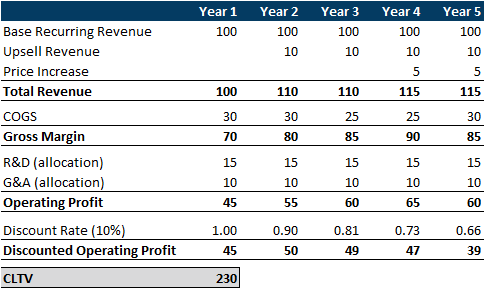

CLTV method 4

This method isn’t a single formula; rather, it involves performing a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis based on either A) gross margin, or B) operating profit. The goal is to calculate the net value for a typical customer, and it should be done for a standard customer within each customer cohort or product. It takes into account gross profit or operating profit per individual customer year over year and discounts that value back to present day.

Usage: This method allows a company greater flexibility in adjusting margins over time and allows for future price increases or upsell/cross-sell opportunities. Here’s a simple example:

One example of a company utilizing this method is Workday, Inc., which provides enterprise cloud applications for finance and human resources. During an analyst day presentation, Workday’s CFO highlighted the present value of the 10-year value of a customer (discounted at eight percent). The context around this exercise was to highlight the lifetime value of two customers: Customer A, which is a core HR customer, and Customer B, which is a full platform customer.

He compared the present customer value of each ($7 million for A and $23 million for B, assuming no upsell or cross-sell) relative to the cost to acquire each respective customer. Workday uses these calculations to highlight the value of each customer segment, and knowing the value of each customer segment becomes more insightful when we understand their corresponding customer acquisition cost (CAC) metrics [endnote 2].

Customer acquisition cost (CAC)

The other side of the coin from CLTV is customer acquisition cost (CAC), which examines the expenses incurred to obtain a new customer. It doesn’t matter how valuable a customer may be if it can’t be acquired profitably. Following are three methods for calculating CAC, starting with the simplest approach and then increasing in complexity as they progress:

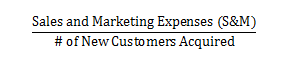

CAC method 1

This is the simplest and most common approach used currently. It takes the amount spent on sales and marketing (S&M) activities and divides that by the number of new customers acquired.

While it seems straightforward, there are a couple of things to keep in mind:

- Similar to CLTV, time frames need to correlate and the number of customers should either be quarterly or yearly.

- The number of new customers acquired should also take into account the number of customers lost and replaced due to churn. For example, if there were 100 customers at the end of Year 1 and 150 at the end of Year 2, the number of new customers may not simply be 50. If 10 customers were lost during the year, then the number of new customers that S&M acquired was 60.

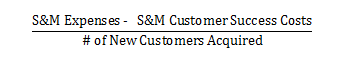

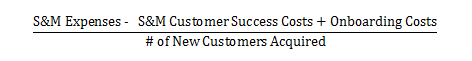

CAC method 2

Not all S&M expenses go towards acquiring new customers. This approach builds on the previous method to remove the portion of S&M expenses that go towards retaining or growing existing customers, which we group into customer success costs.

Note: If you include upselling and cross-selling within your CLTV (as in the CLTV method 4 example), then you will want to keep some or all of the S&M customer success expenses in your CAC. When evaluating CLTV and CAC together, it’s important to stay balanced and ensure that the source of the revenue in CLTV is captured in the cost of acquiring that revenue in CAC.

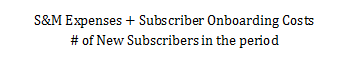

CAC method 3

This calculation approach takes into account that there may be other costs to consider when actually securing a customer. These can include onboarding or professional services costs that are used to support customers during free trials as well as onboarding. If these expenses are not being captured in the gross margin percentage of your CLTV calculation, then they need to be included as part of your acquisition cost to ensure completeness.

In revisiting the MINDBODY example, we see that it accounts for onboarding costs in addition to S&M costs. Specifically, MINDBODY shares the following calculation [endnote 1]:

Combining CLTV and CAC for greater insight

CLTV and CAC are most powerful when used in tandem to tell you how much value you’re deriving from your customers and to identify which customer cohort or product is the most valuable.

When CAC is greater than CLTV

If your CAC is greater than your CLTV, then you’re spending more to acquire customers than you are getting back from them. This may be fine in the short term for early-stage, rapid-growth companies, but it is not sustainable in the long run. It is especially dangerous if you have limited expenses reflected within your CLTV calculation (such as in CLTV methods 1 and 2).

If you find yourself in this position (or close to it), you need to ask yourself why and think about the following:

- How do I acquire customers more cheaply? Am I targeting the right segments, using the right channels, etc.?

- Am I pricing my core product properly, or am I potentially leaving money on the table?

- How can I further monetize my existing customer base? Are there other offerings, services, training, etc., that may appeal to them and increase their lifetime value?

When CLTV is greater than CAC

If your CLTV is greater than your CAC, you are profitably acquiring customers but still need to examine it further. The rule of thumb tends to be, a CLTV that is three times greater than your CAC is a positive indicator for your business model. If you are less than 3x, then you still may want to explore either reducing your CAC or increasing your CLTV.

If you have a CLTV-to-CAC ratio greater than three, then there is a different set of questions you should ask:

- Should I be investing more in growth? Increasing acquisition costs to get additional profitable customers can be a potent strategy if the CLTV:CAC ratio stays reasonable.

- Am I missing something? How much will it cost to retain that customer over its lifetime?

- Am I relying too much on the later years of my customer relationship to drive the majority of the CLTV?

These last two questions require a bit more explanation: Imagine you’re using CLTV methods 1, 2 or 3 to calculate the lifetime value, which use churn rate as a proxy for length of the customer relationship. This assumes:

- If you have a customer churn rate of five percent, then mathematically you’re assuming that you will still have 60 percent of Year 1 customers after 10 years and 36 percent of Year 1 customers after 20 years.

- If you have a churn rate of 10 percent, you are assuming you still have 35 percent of Year 1 customers after 10 years and 12 percent of Year 1 customers after 20 years.

It’s hard to imagine that even enterprise customers can be retained for 10+ years without significant additional investments in product enhancements, sales re-acquisition, and customer success. If you find that you are overly reliant on the last years of a customer relationship, you should look to break even on your customer acquisition costs within the first two to three years of your relationship. This can be accomplished by either driving down CAC or looking to boost customer value within the early years of the relationship.

Bringing our MINDBODY example full circle, the company touts its improving ratio of subscriber lifetime value to cost of acquisition (>5:1), highlighting its impact on simultaneously growing the business and generating future cash flows (endnotes 1, 3].

Workday also puts the CLTV for both customer types (Customer A, whose CLTV is $7 million and Customer B, whose CLTV is $23 million) in the context of their respective acquisition costs. In particular, Customer A’s CLTV-to-CAC ratio is 7:1, whereas Customer B’s CLTV-to-CAC ratio is 10:1. While both of these ratios are strong individually per our guidelines, Workday’s comparison between the two products also helps to communicate the relative value its product mix is generating (endnote 2].

The Workday example also highlights the importance of measuring CLTV and CAC by customer segment, cohort, product or other segmentation approach. This helps highlight which segments are the most valuable and merit further investment and which segments are the least profitable and require adjustments.

Another interesting example of how the CLTV-to-CAC ratio is leveraged to provide insight into operations was stated by Constant Contact, a company that provides online marketing tools for small businesses, nonprofits and other associations globally. In its Q2 2015 earnings call, the CFO explained an increase in the proportion of lower-ARPU customers as follows:

“While these customers often have lower ARPU, they generally have a meaningfully lower cost of customer acquisition and better retention rates, driving higher customer lifetime value. The impact weighs on ARPU growth in the near-term, but should be outweighed by medium-term gains in customer lifetime values.”

While the decrease in ARPU would typically be viewed with concern, viewing it through the lens of CLTV and CAC illuminates that the business stands to benefit from gains in customer lifetime value [endnote 4].

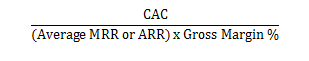

One additional consideration related to CAC and CLTV is payback period, the expected break-even timeframe in months or years in which CAC is repaid. Simply divide CAC by the top half of your CLTV calculation. The time frame used in the CLTV (either months or years) will dictate whether the payback period is in months or years. For example:

Ideally you will have a payback period less than your average contract length. If you have a payback period over two years, you may be relying too heavily on the later years of a customer relationship to drive profitability.

Conclusion

While the methods and insights detailed above serve as a good starting point and frame of reference for most companies, it is important to note that specific calculation approaches will depend on a given company’s operating model, strategy, maturity and structure.

Furthermore, we have seen that additional insights can be uncovered by performing these calculations by segment, whether it be cohort, product, geography or any other logical segmentation for your business.

These insights are not only useful in explaining your business and breaking down your current state, they are also powerful in informing future decisions.

Endnotes

- MINDBODY, Inc. Analyst Presentation, November 2015

- Workday, Inc. Analyst Day, September 29, 2015

- MINDBODY, Inc. Q3 2015 Earnings Call, November 4, 2015

- Constant Contact, Inc. Q2 2015 Earnings Call, July 23, 2015

Andrew Loulousis is a manager at Waterstone Management Group LLC. He advises clients on a number of key strategic issues including growth planning, operations improvement, outsourcing, new product design and launch, customer success strategy and design and acquisition diligence. Contact him at aloulousis@waterstonegroup.com.

Aman Singh, senior associate at Waterstone, also contributed to this article. Aman specializes in delivering value to clients through quantitative and qualitative analysis. He has contributed to the development of the firm’s customer success offerings and has performed market analysis across a variety of technology markets.