You may have noticed that unicorns don’t seem so rare anymore.

In fact, with VC funding on pace to top $100 billion for the first time since the dot-com days, according to the latest PitchBook-NVCA Venture Monitor, it seems it’s never been a better time to fund a billion-dollar startup. But what if those startups never mature into real businesses with real profits?

What if the VC industry is in fact funding future pain, not unlike mortgage brokers a decade ago and Pets.com investors during the bubble, prepping for disappointment at best and economic downturn at worst?

That’s the question posed by Martin Kenney and John Zysman—of the University of California, Davis, and the University of California, Berkeley, respectively—in a recent working paper titled “Unicorns, Cheshire Cats, and the New Dilemmas of Entrepreneurial Finance?” and reported by PitchBook. Kenney and John Zysman argue that volatility in the market for tech stocks isn’t simply the result of hype coming down to earth, but the consequence of “certain basic flaws in the present dynamics of entrepreneurial firm formation.”

Instead of winning unicorns that could emulate the near-monopolies of Apple and Facebook and the massive capital gains that resulted, VC investors may instead be funding a bunch of loser Cheshire cats—bloated by overvaluation and likely to disappear, leaving just a smile in their wake.

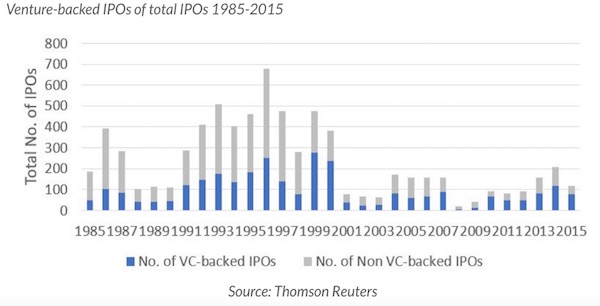

As noted in their paper, the past few years have been marked by easy capital and a fetishization of the early-to-middle parts of the tech startup lifecycle. There are lots of incubators and accelerators, not so many businesses that are on ground solid enough to attempt a public offering. The result has been a steady decline of publicly traded companies.

Why is this a problem? Because private firms aren’t held to the same standard as existing publicly traded competitors who must answer to investors worried about cash flows and operating earnings every three months.

According to Kenney and Zysman, the uneven playing field and influx of capital into the VC ecosystem create a situation where “money-losing firms can continue operating and undercutting incumbents for far longer than previously.

“Arguably, these firms are destroying economic value. This new dynamic has social consequences, and in particular, a drive toward disruption without social benefit. Indeed, in some cases, they may be destroying social value while also devaluing labor and work in the enterprise.”

Furthermore, the wealth associated with this type of investing isn’t distributed fairly through the economy via the public markets, which has an overall dampening affect on the economic engines of growth.

And compare that to the overreaches of the past—too many railroads, too much fiberoptic cable, too many homes. At least something was left behind for consolidators to buy on the cheap and turn into new businesses. What will be left behind for the sharing-, software- and app-based businesses typifying this cycle? A fleet of rusty ride-share scooters?

The good news is that the industry seems to understand the status quo isn’t healthy and, via the NVCA, is pushing policymakers to help fix it. The question is: Will pols hear the call, especially in an election year?

Clare Christopher is editor of SandHill.com.