Given the rhetoric and column inches invested in the subject, it seems strange that anyone is still asking “What is innovation?” Yet, in meeting after meeting, leaders ask this surprisingly frequent and urgent question. Why the fuss? Perhaps it’s because every executive in the world has been told they must either innovate or die.

The meaning of innovation may be fuzzy, but organizations set aside big budgets for “innovative” work.

Debating definitions is usually a fool’s quest, but this is one that needs to be sorted out. In The Rise of the Serial Innovator, we described a global creative transformation that’s driving a new innovation-fueled economy. Too many complex and challenging discussions lie ahead for us to leave the underlying meaning of innovation up for grabs.

Ideally a good working definition would be simple and pragmatic. It should embrace proven methodologies yet have space for creative new approaches. Let’s start by looking back at three effective (but very different) models of innovation; then let’s look forward to an exploration of where innovation needs to go in the months and years ahead.

A simple, utilitarian definition of “innovation”

Begin by drawing a line between change and creation. When people talk about innovation, they aren’t imagining routine change. Simply implementing accepted best practices falls into the category of good management, not innovation. Innovation, at its heart, is an original creative act.

But simply being new is not enough. People care about innovation because it offers important answers to critical business challenges. Innovation must be more than clever; it must be useful in a meaningful way.

These two insights may be enough for a pragmatic definition, the distilled core of what people mean when they say innovation – “Innovation is any practice that leverages creative invention to respond to an important challenge.”

Over the last 70 years, as major market challenges emerged, they drove new generations of innovation strategy. Following this journey should help clarify what is implied by our simple definition and set the stage for exploring a revolutionary economy grounded in repeated and increasingly complex innovation.

R&D labs: ivory towers feeding mass market investments

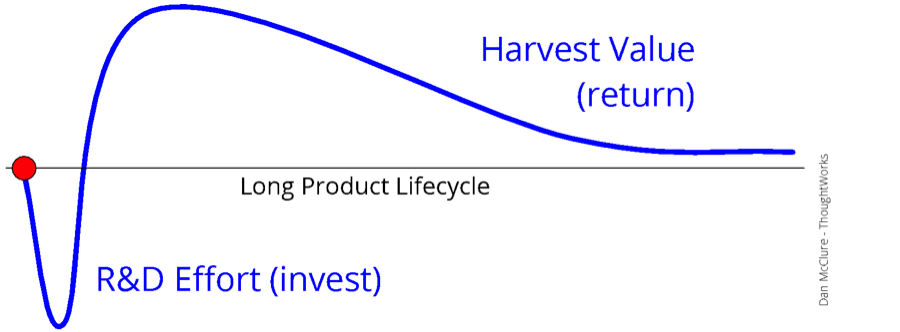

In the mid 20th century, the dominant business model leveraged large capital investments to serve mass markets at scale. Inventions were “discovered” and then “commercialized,” with cutting-edge science often driving the direction of the work.

Discovering these big-ticket investments justified dedicated teams of highly specialized experts focused on advanced innovations. Historically, best practices isolated these ivory towers of research from the rest of the organization.

Today, the model seems archaic. It’s not nimble. Nor is it customer centric or broadly collaborative. According to current dogma, these practices are just “wrong.”

But, be careful. Assuming otherwise smart people are bad innovators is dangerously presumptuous. There are reasons well-established patterns emerge. In fact, here is the first lesson, or simple rule, from our pragmatic definition of innovation:

There is no “one right way” to innovate. Innovation practices are shaped by the business challenge they solve. The definition of a “good” innovation technique is context dependent.

R&D labs address a particular business challenge. They produce powerful ideas with big market impact and justify big downstream investments. This work can’t be done through market surveys or shop floor suggestions. Customers were never going to invent transistors for Bell Labs.

As far back as 1957, in “The Organization Man,” William H. Whyte railed against organizational policies that “fight against genius.” Yet even though he fervently called for granting researchers greater intellectual independence, he didn’t seek to set them free of their labs. The basic R&D lab model made sense in the context of the current business challenge.

Today, many startups are effectively independent R&D labs, purchased when they demonstrate an invention worthy of big ticket commercialization. As a teenager, Palmer Luckey accumulated 50 different head-mounted displays in his home lab and began prototyping the Oculus Rift virtual reality device in his parents’ garage. From this two-car ivory tower he produced an invention worth $2 billion dollars to Facebook.

R&D labs are far from dead, but they are not the only model of innovation available to us.

Lean manufacturing: incrementally optimizing operations

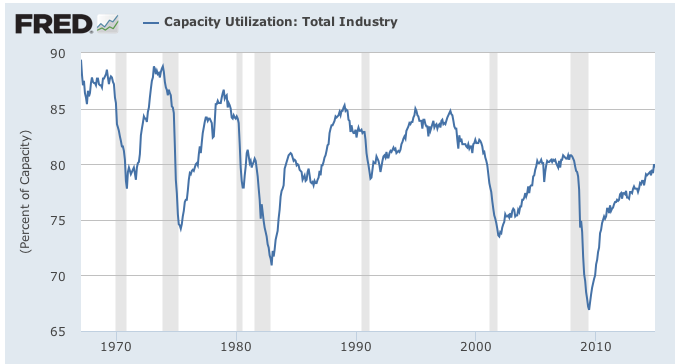

Fast forward to 1970. As the world recovered from the ravages of World War II, global industrial capacity ballooned. In just two decades, China alone multiplied its industrial output by a factor of 25. As capacity poured onto the world market, U.S. industrial utilization experienced deep fluctuations overlaid on an extended downward trend, as illustrated in the graphic below.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

This was a new type of challenge. Too many factories were chasing too few customers. Surplus capacity was particularly hard felt in the automobile industry, which was thrown into turmoil by falling prices and idle capital assets.

The big automotive brands couldn’t unbuild their factories. Huge investments were already in place. What they needed was a value proposition that leveraged their assets while differentiating their products in an overcrowded market.

Enter W. Edwards Deming. He began working in Japan shortly after World War II and developed a series of techniques to systematically improve production quality and reduce waste. His model of lean manufacturing was enthusiastically embraced by Toyota, which leveraged Total Quality Management (TQM) to drive incremental process and design improvements across its production operations.

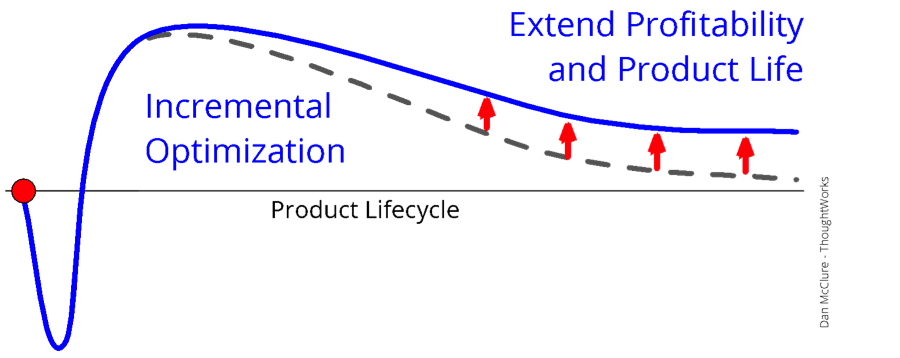

With incremental improvements to existing value propositions, organizations could lift profitability and extend the economic life of established products. These techniques made inroads at democratizing innovation, pulling creative invention from the R&D lab and bringing it onto the factory floor. The massive operational complexity of a production line was captured in detailed process documents and performance was rigorously measured. With this foundation in place, a workforce with a narrow but intimate view of their jobs could make valuable incremental improvements.

According to the International Organization for Standards, “ISO 9001:2008 is implemented in over one million companies and organizations in over 170 countries.” So it seems strange that many question whether these small incremental advances are really innovation at all. Here’s another area where a simple pragmatic definition can help untangle the knots of an unproductive debate: Put simply, the second rule is:

Size doesn’t matter. If a creative invention solves a key organizational challenge, then it’s innovation, regardless of how big or small the idea is.

Lean manufacturing leverages incremental improvements to extend the life of major business assets. That’s creative, original and valuable. It may not always be flashy, but there is no reason to exclude these inventive acts simply based on the magnitude of the change.

Lean Startup: exploring greenfields of opportunity

Now, step forward two more decades. In the 1990s, a new greenfield opportunity exploded on the scene. The Internet created a rich unexplored space with untapped potential. It was a land-rush economy where speed and “seat-of-the-pants” creativity delivered the best rewards.

The methods popularized by Eric Reis in “The Lean Startup” favored fast-moving experiments and minimum viable products (MVPs) to quickly test market opportunities. The source of insight shifted too. User-Centered Design (UCD) and Design Thinking put the customer at the center of the discovery process. Smart designers set aside their hubris, testing ideas with real people so they could fail fast and learn quickly.

Discovering product-market fit favored small, empowered teams that could quickly pivot their approach based on the latest learning. Neither R&D labs, with their detached and plodding progress toward big mass-market initiatives, or Lean manufacturing’s tightly documented operations provided a suitable innovation model for this market challenge.

A new business problem (quickly exploring untested market opportunities) drove a new approach to innovation. Taken more broadly, this becomes the third insight, or simple rule from our simple definition.

New challenges drive new strategies. As new challenges arise with different constraints and opportunities, new innovation models will evolve to serve them.

Pizza and Red Bull fueled a 20-year explosion of technical product development. As the dot-com gold rush played itself out, the 2007 launch of the iPhone stepped in to create a new round of opportunities perfectly suited to fast-moving Lean Startup innovators. Eventually, wide open markets reach a point of saturation. With 1.4 million apps for the iPhone and the Android (as of July 2014), it’s hard to imagine that many more simple products are waiting to be developed.

The next innovation revolution

So what’s next? These three models solved important business challenges in their day, but there are still important problems where innovation could do far more than it has.

- Scaling innovation – Many promising pilot programs fail to go to scale and thus remain small and largely inconsequential experiments.

- Big messy problems – Complex problems with multiple dimensions, such as innovating in areas of persistent poverty, are often intractable.

- Enterprise innovation – Big organizations need to prove Clayton Christenson wrong, making size a virtue. But how do they innovate across an enterprise with deep legacy systems and cultures?

- Collaborative business models – New technologies create the opportunity for uniquely designed business collaborations. How do you innovate with diverse people you just met?

The unifying theme in this list is complexity. They are all wicked problems in ill-behaved messy domains. Existing innovation models weren’t designed to deal with these challenges, yet these are the areas of greatest opportunity in the coming innovation-driven economy.

The ideas in a nutshell

Here’s a summary of the ideas in this article.

A simple definition: Innovation is any practice that leverages creative invention to respond to an important challenge.

Some simple rules:

- There is no one right way to innovate

- Size doesn’t matter

- New challenges drive new strategies

Three strategies for three challenges:

- R&D lab – Inventing big new ideas that support big capital investments and long-term business commitment

- Lean manufacturing – Incremental improvements in proven business operations to sustain the life of a value proposition

- Lean Startup – Rapidly discovering product market fit in greenfield opportunities

Next … embracing complex innovation

This is the second of a series of articles examining the transformational challenges and opportunities ahead for creative innovators. The first article, The Rise of the Serial Innovator, described global forces that are moving innovation to center stage in transformed world economy.

Responding to this economic shift requires a dramatically expanded ability to innovate in complex domains. We’ll begin to explore that challenge in the next article, “The Unmet Challenge of Complexity.” Sign up here for the ThoughtWorks Innovation Series.

Dan McClure is the innovation design practice lead at ThoughtWorks. He has extensive experience and enthusiasm for blowing up the status quo. He has spent over 30 years as an insurgent innovator for organizations ranging from automotive manufacturers to educational institutions. Today he leads innovation design for ThoughtWorks in North America.