Startup boards are complex. While all board members own stock in the company their interests are not necessarily aligned.

Startup boards are complex. While all board members own stock in the company their interests are not necessarily aligned.

- Founders may be motivated by a vision to change the world, to hit a certain net worth target, to see their name in an S-1, to make the Forbes 500, or — and I’ve seen crazier things — to make more than their Stanford roommate. First-time founders with little net worth can be open to selling at relatively low prices. Conversely, serial successful founders may need a large exit simply to move the needle on their net worth. Founders can also be religious zealots and take positions like “I wouldn’t sell to Microsoft or Oracle at any price.”

- Independent board members typically have significant net worth (i.e., they’ve been successful at something which is why want them on your board) and relatively small stakes, which, by default, financially incents them to seek large exits. While they notionally represent the common stock, they are often aligned with either the founders or one of the investors in the company — they got on the board for a reason, often existing relationships — and thus their views may be shaped by the real or perceived interest of those parties. Or, they can simply drive an agenda that they believe is best for the company — whatever they happen to think “best” means.

- Venture capitalists (VCs) are motivated by generating returns for their funds. Simple, right? Not so fast. VC is increasingly a “hits business” where a few large outcomes can mean the difference between at 10% and 35% IRR over a fund’s ten-year life. Thus, VCs have a general tendency to seek huge exits (“better to sell too late than too early”), but they are also motivated by other factors such as the expectations they set when they raised their fund, the performance of other investments in the fund (e.g., do they need a big hit to bail out a few bad bets), and their relationships with members of other funds represented on the company’s board.

In this light, it’s clearly simplistic to say that everyone is aligned around a single goal: to maximize the value of the stock. Yes, surely that is true at one level. But it gets a bit more complicated than that.

That’s why it’s so important that CEOs ask the board one question: What does success look like?

Somewhat amazingly, this question is rarely asked. And even if it has been, it doesn’t hurt to re-ask this very important question every few years as any given board member’s position may change over time.

I’m always shocked how the simplest of questions can generate the most debate.

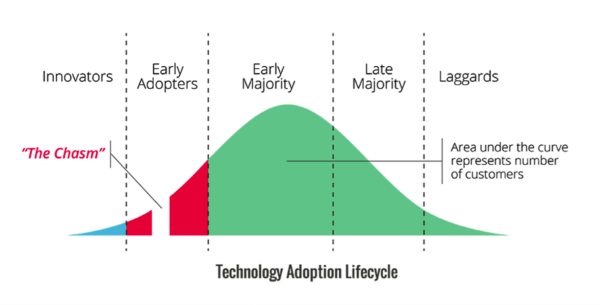

Back in 1998 when I was at Business Objects, I suggested bringing in the Chasm Group to help us with a three-day, strategic planning offsite. I figured the executive team would spend a morning reviewing the key concepts in Crossing the Chasm, at most one afternoon generating consensus on where we sat on their technology adoption lifecycle curve, and then two days working on strategic goals and operational plans after that.

Even though this team had worked together closely for years, we never agreed where we sat on the curve despite three days of debate. We spent literally the entire time arguing, often intensely, and never even got to the rest of the agenda. Fortunately, that didn’t end up impeding our success, but it was a big lesson for me.

So be ready for the “What does success look like?” question to generate a long answer. Most probably, several long answers. In fact, in order to get the best answer, I’d suggest asking board members about it first individually (to avoid any group decision-making biases) and then discuss it as a group.

But before examining the answers you can expect to this question, let’s take a minute to consider why this conversation doesn’t occur more often and more naturally. I think there are three generic reasons:

- Conflict aversion. Perhaps sensing a misalignment of values – not unlike what might be found in a bad marriage – the CEO and board tacitly agree to not discuss the problem until they must. You may hear or make excuses like, “Let’s cross that bridge when we come to it,” or “Let’s execute this year’s plan and then discuss that,” or “If there’s no offer on the table then there’s nothing to discuss.” Or, in a more Machiavellian situation, a board member may be thinking, “Let’s ride Joe like a rented mule to $5M and then shoot him,” continually deferring the conversation on that logic. The reality? Pleasant or unpleasant, it’s usually better to address conflicts early rather than letting them fester.

- Rationalization of unrealistic expectations. If some board members constantly refrain “This can be a billion-dollar company,” perhaps the CEO rationalizes it, thinking “They don’t really believe that; they’re just saying it because they think they’re supposed to.” But what if they do believe it?

- The gauche factor. Some people seem to think it’s a gauche topic of conversation. “Hey, our company vision statement says we’re making the world a better place through elegant hierarchies for maximum code reuse and extensibility, we shouldn’t be focusing on something so crass as the exit, we should be talking about making the world better.” VCs invest money for a reason, they measure results by the IRR, and they can typically cite their IRRs (and those of their partners) from memory. It’s not gauche to discuss expectations and exits.

When you ask your board members what success looks like, these are the kinds of things you might hear:

- Disrupting the leader in a given market

- Building a $1B revenue company

- Becoming a unicorn

- Changing the way people work

- Getting a 10x return in 5-7 years for an early stage fund, or getting 3x in 3-5 years for a later stage fund

- Showing my mother my name in an S-1 (a sub-case of “going public”)

- Getting our software into the hands of over 1 million people

- Realizing the potential of the company

- Selling the company for more than I think it’s worth

- Getting acquired by Google or Cisco for a price above a given threshold

- Building a true market leader

- Creating a Silicon Valley icon and/or a household name

- Selling the company for a base-hit, double, triple, home-run, or grand-slam outcome.

Given the possibility of a list as heterogeneous as this, doesn’t it make sense to get this question on the table as opposed to in the closet?

I learned my favorite definition of strategy from a Stanford professor who defined strategy as “the plan to win.” The beauty of this definition is that it instantly begs the question “What is winning?” Just as that conversation can be long, contentious, and colorful, so is the answer to the other, even more critical question: What does success look like?

Dave Kellogg is CEO of Host Analytics. This article originally appeared on his blog.