The Internet of Things (IoT) is a modern day gold rush. In the technology world, the IOT offers a vision of new and better products and services delivered at lower cost. But who will make money? Let’s look at a couple of examples and try to characterize the entrepreneur’s “gold rush dilemma” — shall I dig for gold, or shall I sell shovels to the miners?

Let’s start with the gold, or at least one small segment of it — service revenues for machinery manufacturers. In 1962 Rolls-Royce introduced a new business model for servicing jet engines. Later called “Power by the Hour,” the offer was a complete engine and accessory repair and replacement service offered at a fixed price per flying hour. Over the last 10 – 15 years, real-time air-to-ground transmission of engine sensor readings has enabled Rolls-Royce and other jet manufacturers to extend their range of service options with a monitoring service; ground-based engineers keep an eye on the readings and can offer advice to pilots if needed.

The IoT enables every machinery manufacturer to develop their business model for service along these lines. Remote access to machines and machines that can report relevant status information are possible at affordable costs. Add a willingness to rethink the commercial basis of servicing, and you are poised to disrupt the market.

To see the potential for a machinery manufacturer, you have to look at the existing service arrangements. Many manufacturers have built their businesses using distributors and resellers to increase their sales reach. This has usually involved devolution of installation, service and repair activity — and revenues — to the resellers.

For the manufacturer, IoT offers a route to take over this revenue stream, offering cost savings and a better user experience. So this is IoT gold — a new, profitable revenue stream. Even for manufacturers that handle sales and service direct, the cost savings and user experience improvement represent competitive advantage and better margins — still gold, but incremental rather than new.

What are the steps to open up this revenue stream? Of course, each machine will need a network connection and the capability to report useful status information. In the case of a jet engine, the costs of doing this are substantial but small compared to the capital, service and loss-of-service impact costs. So jet manufacturers have found it relatively easy to justify the in-engine sensors, the satellite communications channels to report readings and the secure IT systems to collect the data.

This is exactly where the technology for IoT has transformed the cost side of the equation, and opened the opportunity to almost every machinery manufacturer. For example, there will be machines where the only parameter that needs to be measured is the electricity usage. This might be as simple as on/off monitoring; but if you measure the profile of electric current, you may get useful information about the state of the motors and the load being put on the machine. There’s probably a characteristic current profile signature that happens before a breakdown. To capture this, product development may be as simple as a new power cord, one that contains the current monitoring circuitry and a wireless network capability. You can retrofit the new power cord to existing machines in the field as well as use it for new machines.

The next step is to make the connections to your data center. And this is a challenge – will you have 10 or 10,000 machines to monitor? On day one, you don’t know. Fortunately, the technology drivers behind IoT have an answer: the cloud. Build your monitoring applications for the cloud and you don’t need to calculate server sizes or make investments to cover peak capacity before you start. With the cloud, you can pay as you go for the server capacity you need.

Now you will be able to deliver better service for less; by monitoring the machines, the need for service can be predicted and delivered before the machine fails. Rather than phone to arrange the annual service, the call that says “look at the start-up current consumption, we’ll need to replace the bearings within a month” probably gets better customer satisfaction scores.

In addition, if machine locations are known (or perhaps reported by a GPS in the power cord), then every day the manufacturer can optimize travel plans for field service personnel. And if the current profile is a good-enough record of machine usage timing and load, then these parameters can be built into a “power-by-hour” type of service contract. Customers recognize that this is the type of service contract that puts motivations in the right places (more profit for the service provider if the machine never breaks down).

If all the intelligence can be put into the power cord, there’s a business case for low-cost machines.

More expensive machines probably have existing electronic controls, and you’ll get more machine status information if you upgrade the controller hardware and software to capture and report not only electric consumption but also other sensor readings.

So, for machines across the cost spectrum, “Thar’s gold in them thar hills!”

But what about the shovels? Let’s switch attention to embedded software development tools. In this context, these software development tools are one of the many different types of “shovel” that the IoT miners need. Embedded software development tools are used to create the software inside the machines. So, for the examples above, this is the software that is part of the power cord circuitry (managing the electric current sensor and the network connection) and also the software inside the machine controller (doing the same job and also providing the control functions for the machine).

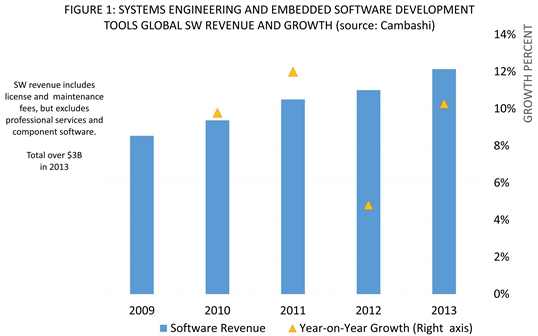

Software license and maintenance revenue for these software tools is now over $3 billion, and growth continues to average over nine percent every year (see fig. 1).

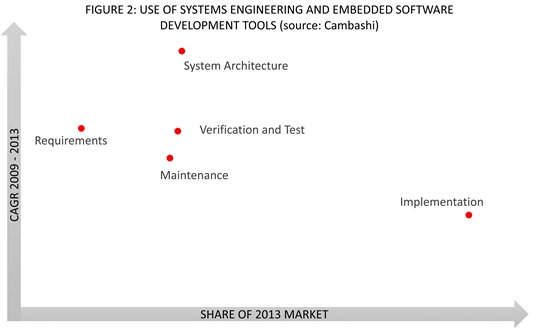

Figure 2 classifies the 2013 revenues according to major use categories and plots average annual growth rate against share of this market. You can see implementation tools make up a large part of the market, but this category has a lower growth rate than the growth leader, systems architecture.

Of course, these tools are used for all types of embedded software, not just for the embedded software needed to make IoT a reality. So any interpretation of these figures is a comment on the broader embedded software development market, within which IoT is an important driver and frontier.

Let me suggest an explanation. The embedded software market is maturing. The emphasis on just making software work — implementation — is less critical than it used to be. Engineers have this under control. Instead, the growth of complexity across electronics, hardware, software, communications and complexity of partnerships with suppliers and partners are aspects that increase the emphasis on requirements and system architecture.

Of course, the evidence is the figures. My explanation is a just a hypothesis. But in a gold rush, being left behind is the risk an entrepreneur fears most, so a hypothesis may be all they need.

Peter Thorne is managing director of Cambashi. Peter has applied information technology to engineering and manufacturing enterprises for more than 20 years, holding development, marketing and management positions with both user and vendor organizations. Immediately prior to joining Cambashi in 1996, he headed the UK arm of a major IT vendor’s engineering systems business unit, which grew from a small R&D group to a multimillion-pound profit center under his leadership.