This article describes an “annual checkup” you can use to assess your engineering outsourcing relationships. There are two reasons it’s a good idea to do such an assessment. First, situations change. If your business has grown, you may be in a position to upgrade to a higher class of vendor. Other needs may have changed as well. Second, you (or your predecessor) may have made a suboptimal choice in the first place, then allowed inertia to carry it along.

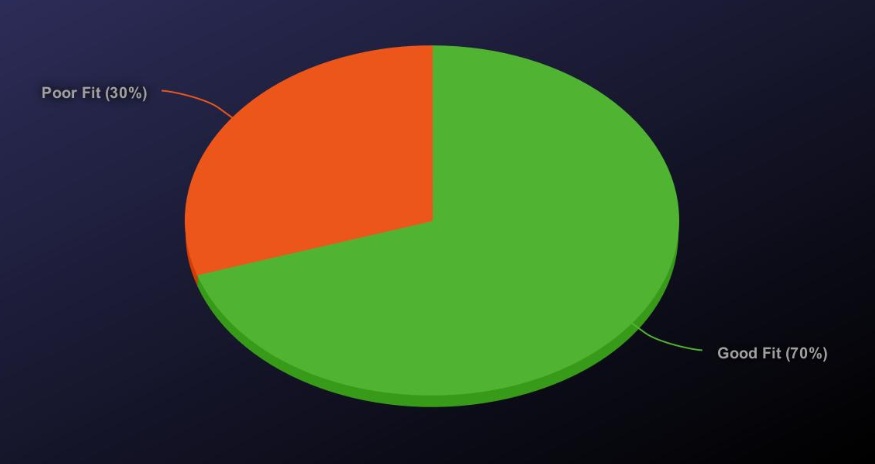

In our experience, nearly a third of vendor relationships are a poor fit. We commonly see clients engaged with vendors that are too small and immature, too large and difficult to work with or that lack important skills that keep the relationship from delivering full value. If you’re among the 70 percent of companies whose vendor is well suited to their situation, there are still ways to optimize your relationship and improve your outcomes.

Here, then, are six questions you can ask your vendor, and your own team, to assess how you can get more out of contract engineering and whether it may be time to look for a firm that better fits your needs.

1. How much turnover has my contracted team experienced in the last 12 months?

High turnover is the biggest complaint of companies that hire contract engineering firms. Turnover kills productivity – even if the vendor absorbs the cost of ramping up replacement engineers, inevitably there is schedule delay and extra load on the client.

Turnover of more than 10 percent annually on your project team is a yellow flag; more than 20% should be a red flag. High turnover indicates one of several issues:

- The vendor is rotating engineers away from your projects too frequently. Some amount of rotation is expected: it’s inherent in the contract business model, and it may even benefit your project if a bright engineer with a fresh perspective joins the team from time to time. Excessive rotation, though, is a problem. It often indicates that the vendor is too big for you and it is favoring larger clients at your expense.

- The vendor is having trouble retaining employees. In the most popular locations – Bangalore, for example – the business climate encourages employees to jump from firm to firm. The best firms can attract and retain strong talent; others can’t.

- Employees are asking to be reassigned. If the type of work they’re doing isn’t what they want to do, engineers will ask to be rotated. Usually the work isn’t the problem; the problem is the match between the work and the people your vendor assigned to it.

Red Flag: If you’re seeing more than 20 percent turnover, that’s an indication of poor fit.

There are vendors out there that have the right staff for your project and manage that staff effectively to provide you the continuity you need.

2. What percent of the vendor’s total business does my company represent?

You want to be a big enough part of the vendor’s business that you matter to it, so you get proper attention. Vendors will move heaven and earth to satisfy their top-10 or top-20 clients – which generally means those clients that generate more than one percent of their annual revenue. If your account represents a small fraction of one percent of a vendor’s business, you will almost certainly get better service from a vendor right-sized for you.

Is it possible to be too big a fraction of your vendor’s business? If you contribute more than 30 percent or 40 percent of the vendor’s revenue, you’ll certainly get lots of attention. Being such a large client might constrain your flexibility, though. Part of the appeal of contract engineering is that you can ramp up or down when you need to; that can be difficult when your budget cut can put your supplier out of business.

Red Flag: Working with an immature vendor means you’re sacrificing rigor.

Even if you’re not at the 30 to 40 percent level, working with a vendor that is small relative to your project size may mean you’re sacrificing rigor. Small vendors usually have less mature project and people management than larger vendors. If your vendor is scrappy but inconsistent and your business is large enough, consider upgrading to the next tier.

3. What type of deliverables am I getting, with what effort from my internal team?

The key question here is does your vendor need to be managed at the task level, which is difficult to scale, or can the vendor understand and offload larger pieces of work so your own project management bandwidth is not the bottleneck?

The so-called “staff augmentation” model is where many engagements start. In this model, the vendor provides a few individuals that join the client’s team. This model is appealing because it limits your risk, but it also limits the upside you can achieve.

Imagine for a moment that you could consistently get complete components, or even complete projects, delivered by your contract vendor on schedule and with high quality. Clearly that model provides tremendous leverage for your team. The reason that many organizations contract at the staff level rather than at the project level is not because they don’t want higher leverage but because they don’t have confidence that it can be achieved.

Red Flag: If your vendor only provides bodies, you’re missing out on leverage.

Here, again, it’s a question of fit. For most types of work, there are vendors out there that can take a high-level assignment and deliver a comprehensive work product. If your only experience is with vendors that provide members for your team, you have an opportunity to access much better outcomes by finding a suitable project-level partner.

4. How convenient is it to communicate with the vendor?

Considerations here include time zone, language, in-person access and clue. If your project is large enough, you really want one or more onsite liaison(s) who can proxy information to the remote team. If you’ve only worked through conference calls and never had an onsite representative, you don’t know what a luxury it can be. Despite all the advances in communication technology, nothing matches the bandwidth of a face-to-face conversation.

Conversely, if you’ve always had your full team on site, then you’ve always had the burden of managing every individual and you’ve not experienced the follow-the-sun “magic” of a full day’s work happening overnight.

Once your project team is more than a handful of people, a right-fit vendor should provide you with an onsite representative. (Generally we recommend it be someone who also codes; but that may vary depending on the project.)

Short of an on-site representative, the next best thing is having on-demand access to someone that speaks your language and can meet (virtually) in your time zone. And, of course, it’s crucial that your point of contact have serious clue, so things are understood clearly the first time.

Whatever level of communication you have with your vendor, ask what it would take to upgrade to the next level up. Optimizing communication reduces rework and makes everyone more productive.

5. What schedule variance have you experienced on outsourced projects?

While the previous questions were process questions, this is an outcome question. What results is your relationship achieving?

Schedule variance is certainly not the only measure to consider, but it’s an important one. If your actual-vs-plan is far off, that can indicate that your vendor is not the right size, as discussed in question 2. If the vendor is small for you, it lacks the planning capability you need. If the vendor is too large, it may have the capability but reserve it for bigger and more important clients. High schedule variance can also result from poor communication, high turnover or other right-fit issues.

Red Flag: More than 10 percent schedule variance is another sign of fit issues.

6. How often does your vendor meet your need for specialized skills?

Finally, over the course of a long-term relationship, you will have needs for different technologies and skills. In some cases, these will be very specialized or obscure, and you will either need to hire for them or bring on specialized consultants. At the same time, you don’t need the hassle of managing lots of different engagements. Ideally, your primary vendor should be able to adapt to your requirements and handle at least half of your specialized needs. Then a group of secondary vendors can fill in the rest.

There are tradeoffs here, related again to right-sizing your relationship. If your business is small, you’re best with a vendor that will give you attention, and that vendor may not be able to cover many different technologies. As your company grows, you have the opportunity to move to a provider with a broader portfolio.

A regular check-in with your contract engineering vendor, on these topics and others, can highlight areas for improvement and give you signals for when it’s appropriate to look at other providers. If you discover that your vendor isn’t a great fit for you, don’t despair: first, you’re not alone, and second, there are other choices out there.

Spencer Greene has run engineering and product management organizations for large & small companies in Silicon Valley for the last 25 years. He is currently helping clients of eInfochips Ltd get the most out of their outsourced engineering relationships. He can be reached at spencer.greene@einfochips.com and Linkedin.