Investors hate it when I say founding CEOs kill more startups than anything else. Founders aren’t too fond of the statement either.

But a fact it is. Having consulted to many a Silicon Valley startup, and having watched many others high dive directly into the dead pool, one reality kept bubbling to the surface: Even nifty startups with unique products and plenty of VC cash die, and the assassin is often the innovator who created the technology. Many are afflicted with one or more symptoms of a deadly disease I call “founderitis.”

Why would a viable and unique technology product fail? The answer comes from Peter Drucker, the 20th century’s most famous management guru. Never at a loss for a sharp insight, Drucker once said that business has only two basic functions — marketing and innovation. Everything else is administrative work or tech support. The growling noise you hear are the discontented voices of accountants, logistics teams, secretaries, middle managers, bench techs … everyone who was just classified as not part of business.

But Drucker was right. Innovation conceives the product and marketing makes it accessible. (Marketing also helps define the product, but let’s not give those marketing people swelled heads today). Hence, if startup CEOs have innovated and created a product but have no clue as to the basics of go-to-market strategies, they can waste time, market advantage, all their investor’s lucre and drive their staffs to drink (well, for the marketing people it is not a drive, but a short walk).

The point is that startup CEOs generally know nothing about marketing.

Drucker’s observation fits nicely with what my old man used to tell me. Being an engineer he would write it out as an algebraic equation. He was fond of formulating me:

p(s) = 1 – p(f)

The elegant equation says that the probability of success equals one minus the probability of failure. Reduce the latter, and the former becomes difficult to avoid.

Given that Drucker was right, that a full half of business is marketing, then the probability that your average startup will fail because the CEO is clueless about marketing is greater than 50 percent. Since most VCs expect only one in 10 of their investments to pay off, it looks like the equation is valid.

So what are the symptoms of founderitis? What is it that causes the common startup CEO to tank his own corporation? Why do so many of them have to celebrate failure?

Here are some of the more common forms of founderitis. If you are a CEO, examine your own go-to-market strategy and see if you have these symptoms. If you work in a startup and your CEO has any of these, polish up your resume.

Bubble vision

In Silicon Valley, founders are typically techies. They have created products from mere niche notions and often have built/coded the core product themselves. They see their product from the inside out.

Sadly the world sees those same products from the outside in.

Simplistic as this sounds, the outcome is complex. One reason many tech startups hype their features and benefits, their feeds and speeds, is because that is what is obvious to the insiders. Whereas the elegance of their creation makes founders preach about the mechanics of the solution, buyers worry about expected outcomes and validation — what is in it for me and how do I know I will get what I want?

Not knowing customer expected outcomes is one of the more serious symptoms of founderitis. Since all marketing communications revolve in some way around what is important to the customer, any interference with that communication process slams sales.

When founders guide their staffs while harping on technical specs, their staffs follow the lead. Founders who cannot guide their marketing people toward finding, articulating and promoting customer expected outcomes, or who through force of will cause collateral to collapse under irrelevant issues (irrelevant from the customer’s perspective) kill sales in the crib.

Hyperopia and myopia

Wall-eyed or cross-eyed, founders often see markets with the wrong focus.

Startups have always had delusions of grandeur, and success stories like Google and Facebook have not reduced such organizational psychosis. The Internet now enables even the smallest of companies to communicate to the world (which has annoyed a lot of the world’s people on the receiving end of the communication).

Hyperopia is a founderitis symptom that makes CEOs want to sell products to everyone, or at least to their alleged total market. Overly aggressive, this symptom causes a startup to burn through amazing amounts of cash, spreading it very thinly over a lot of people who have little or no interest in the nascent product. Even early-majority buyers tend to be in one or two segments, and the whole product for those segments may have no value to all the other segments. Hence time, innovator advantage and staff stamina are wasted.

Interestingly, many founders react like turtles once they see that selling to everyone is a horrible idea, and revert to focusing narrowly on their early adopters. Since these buyers provided the startup early cash flow, founders frequently focus on early-adopter needs and create a really great product for a handful of folks. Conceptually constipated, the product never gets enhanced to fulfill the whole product needs and expected outcomes of majority buyers, and the startup fails or sells off its technology for cheap.

Segmentitus

Founders hate segmenting their markets. Segmenting is essential, prioritizing segments is profitable and getting a startup CEO to do it is nearly impossible.

This is a side effect of hyperopia. Segmenting forces founders to accept something less than conquering the planet and being an overnight billionaire. Many founders dislike such restrictions, resist segmenting their markets, resent having to play into one or two segments and eventually rebel by segment hopping or seeing false similarities between segments.

Oddly, part of the problem is the complexity of segmenting. Founders have dealt with amazingly complex stuff during development, yet seem flummoxed when faced with n-dimensional maps of segments, sub-segments and buyer genotypes (a.k.a. personae). Perhaps because they are too close to the product itself, they cannot comprehend why everyone else cannot comprehend their product (many political ideologues are the same way), much less why different people in different segments do not share the same spiritual product insights (which tends to explain why there are so many religions).

Reigning in founder expectations and forcing them to focus on dominating one segment at a time is tough. Yet failure to do so depletes assets (human, capital and time) and stretches messaging too thin to make a product seem relevant to anyone in particular.

Valueless values

When you simplify things, product marketing deals mainly with communicating value. Assuming a founder is wise enough to narrowly segment and to deliver a whole product for the target market, getting the marketing folks to articulate value often leads right back to recitations of feeds and speeds.

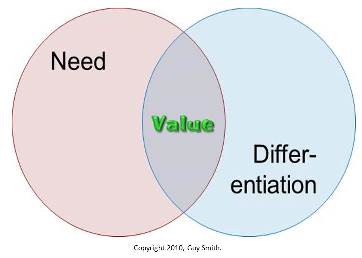

Value (copyright alert) is the intersection of need and differentiation. If a group of people (a segment) share a need (an expected outcome) and your product satisfies that need, articulating anything else misses the mark.

Founders fail at voicing value. Take a look at any 10 startup website landing pages and odds are you won’t find one that has a clear value proposition stated in the headline. It doesn’t matter how killer the product is. If you cannot succinctly describe in the customer’s language why they would find it valuable, then they will have no interest.

Let’s take the classic of all examples, the early Apple iPod advertisements — the dancing silhouettes. Without a single word or even a face, Apple communicated a very personal and real value in those ads. The value was to be elated by your music, wherever you might be. Apple didn’t advertise a flat frequency response from 20-20Khz. They advertised joy acquired through white ear buds — the value of being alive and happy.

In the tech business, founders seem largely immune to attaching emotions to value. This mistake comes in part from being techies and dealing with details. Everyone, even your boss, has emotions. These emotions are directly related to expected outcomes, what they want to achieve, or achieve for their company (the two are often interrelated, as the old adage “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM” shows).

Studies show emotion-only ads outscore rational-based promotions by a leap and a bound. They even outscore ads that appeal to both. Yet tech companies, at least B2B ones, avoid displaying emotions on a sociopathic level.

Wandering brands

Branding is communications. It is (copyright alert again) forcing the market to think and feel what you want them to about your product or company. Branding is more powerful than messaging and biases buyers before the time to decide arrives.

In the early MP3 player days, people entering Best Buy demanded iPods by name, caring not a whit about alternatives or even a better listening experience. Apple branded well.

Founders don’t get brands and rarely take the time to define their brand. This hamstrings progress because brands are communicated through everyone in the organization, not just marketing. Ever hear a nasty sounding receptionist on the other end of a call? How did that affect your perception of the company you were calling? Remember that last tech support call you made where “Dave,” with a thick non-American accent, answered and proceeded to waste an hour of your life not listening to the symptoms your technology was displaying? Same thing.

Related to emotions in value propositions, brands are communications divorced from product functionality. Hence many founders don’t understand it, never define it and leave the market to define the brand. This is bad.

When I took over marketing strategy for SuSE Linux long ago, they had never defined their brand and the market thus assigned them one of “quirkily little German distro.” Not the brand you want when selling to CxOs who are making strategic IT infrastructure decisions.

Promoitis

Also known as “promotion of the week,” this symptom has CEOs chasing whatever promotional mechanism they saw succeed elsewhere without real consideration about its efficacy for their market (which they see too broadly), their target segment (which they never identified or prioritized) or their buyers (upon whose expected outcomes they cannot articulate value propositions).

A while back I chatted with a green CEO in the Big Data space, who was going to market with social media. He based this decision on the success achieved by a different tech company. That other company sold to techies who are very social-media active. The Big Data company sold to CIOs who are not. Hence the odds of repeating the success of socially selling to techies while pitching strategic Big Data to executives are about as good as Britney Spears having another Billboard hit.

The cure

Founders are interesting creatures and hard ones to tame. They know their product inside and out. They know their early adopters well. They have big dreams.

It is the gap between these points in which floundering founders fall.

The cures are few, but effective. The shameless self-promotional cure is for founders to read my book, the “Start-up CEO’s Marketing Manual.” This 30,000-foot view of the seven pillars of go-to-market strategy will give them the knowledge to know the right questions to ask and the requisite checklists to assure everything gets accomplished.

Next, founders need to check egos at the door and unleash their marketing staff, be they internal or outsourced. The CEO’s job is to guide the process, not direct it — to chart a course but let others steer the ship, hoist the mainsail and weigh the anchor. Marketing professionals should have the chops to help define the brand, study buyer expected outcomes, segment and prioritize wisely, advise product development, articulate value propositions and more. Manhandling them is unwise.

Finally, investors need to watch for founderitis and intervene early. Many failed startups could have been saved if early signs of founder-led success interference had been dealt with. Yes, VCs do like their weekly meetings. But this doesn’t assure founders are not unfocused. Watching public displays of messaging, value props and brand will show if the company, and hence the startup CEO, are diseased and if investor inoculation is necessary.

Guy Smith is the chief consultant for Silicon Strategies Marketing and the author of “Start-up CEO’s Marketing Manual.” Guy has led marketing strategy for a variety of technology companies vending high-availability backup software, wireless middleware, enterprise software, infrastructure software, mobile applications, server virtualization, secure remote access, risk management applications, application development tools and several open source ventures. Before turning to marketing, Guy was a technologist for NASA, McDonnell Douglas, Circuit City Corporate Headquarters and other organizations.